When do figurative marks represent the appearance of the goods?

![]()

In the M/S. Indeutsch International case concerning the validity of the “Chevron” device shown above (T-20/16 of 21 June 2017), the General Court held that the mark (described in the registration as “a repeated geometric design”) could not be seen as representing the appearance of the goods for which it was registered, namely knitting needles and crochet hooks in Class 26, but was an abstract shape.

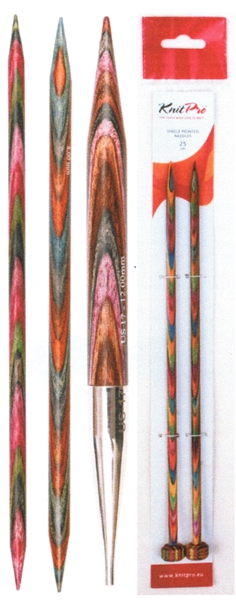

That was in contrast to the Board of Appeal, which had interpreted the registration to be a graphical representation of the pattern as displayed on the actual goods marketed by the trademark owner, samples of which are shown here on the right. As a result, the Board found the mark to lack distinctiveness, as it consisted of a pattern that would be perceived as a mere decoration of the concerned knitting needles and crochet hooks.

The General Court did not consider that the Board’s approach was in line with the law. The key question was whether the Board had to rely on the trademark as registered, or whether it could take into account the trademark owner’s real-life products. That, in turn, had a significant impact on the legal test for distinctiveness: where the mark is a representation of the goods themselves, it has to depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector to be distinctive. Otherwise, for an actual figurative mark or logo, the test is slightly more lenient.

The Court held that a figurative mark and the actual goods could only be set on an equal footing where they differed only in “negligible ways”. That, however, was not the case here (para. 43). As a result, the Court considered that the Board had significantly altered the mark when assessing its distinctiveness, and that this violated the law. The alteration of the mark, according to the Court, had the effect of transforming a mark that was registered as an “abstract shape” into a mark consisting of the specific shape of the goods that it covered (para. 45). By referring to the mark as an abstract shape, the Court itself viewed the mark as a pattern and not merely as a logo; however, it refused to link the mark to the “chevron” pattern used on the goods, despite the evidence and the trademark owner’s own acknowledgement of the same.

The approach taken by the CJEU in the Yoshida Metal case concerning knife handles (C-337/12 P to C-340/12 P of 6 March 2014,) was different, andactually the CJEU set aside the General Court’s judgment exactly on the same point (para. 61): while the General Court annulled the Board’s decision cuchillobecause it referred to representations of the goods actually marketed, the CJEU insisted that one had to take into account the appearance of the applicant’s goods in real-life (the images inserted hereshow both), as confirmed by the applicant’s patents.

In the present case regarding the crochets and needles, there was similarly substantial evidence as to how the mark was applied to the goods. The trademark owner admitted that the mark indeed represented the goods and submitted samples in support of its claim to acquired distinctiveness. The Court focused, however, on the Board’s explanation that the concerned chevron pattern, irrespective of the color, did not significantly depart from “the current custom of representing colored knitting needles and crochet hooks”. The Court interpreted this as relying merely on the color decoration – and therefore alteration of the subject matter of the mark – when assessing the distinctiveness.

The decision of the Board of Appeal was annulled. However, this only affects the Board’s reasoning. If the Board in its new decision maintains that the mark lacks distinctiveness even though it cannot be set equal with the pattern on the actual products, the owner’s claim to acquired distinctiveness is also off the table, as the mark as registered was apparently never used. Hence the adage: “You can’t have the cake and eat it”!